“follow the roads, they lead to ruins”

—gene savoy

In the previous post we’d followed the remnants of an Inca road for four days, crossing a 4500m pass en route to reach Huancacalle. After a rest day there spent exploring the ruins of Vitcos we planned to continue. Our intention had been to follow another 35km or so of very remote Inca road which is now used occasionally as a trekking route to reach Espiritu Pampa, aka the ‘lost city’ of Vilcabamba.

But speaking with the knowledgable Cobos family in Huancacalle we’d learned that during this late stage of the wet season it would be a risky proposition. As we’d seen crossing Abra Mojon, the rivers were all still swollen and it was still raining most days. Furthermore, as they told us, the wet season floods destroy the rudimentary bridges every season and they would not be replaced until the dry season came. To further dampen our plans, we were told that landslides had destroyed part of the track.

This was seriously disappointing news. Anticipating following the final leg of Inca road to reach Espiritu Pampa had been in the back of our minds since leaving Cusco over three weeks earlier. The thought of riding single track from the alpine puna down through cloud forest and finally to the steamy margins of the Amazon lowlands had long been a motivator. It was supposed to be the glorious culmination of our nearly 500km ride through some of Peru’s gnarliest mountain terrain.

But as we sat in the warmth of the Cobos’ kitchen that morning, their son Fredy concluded his bad news with the suggestion that taking the road there instead might not be such an anticlimax. Not only was it a single lane mountain road that crossed a 3820m pass, but it was currently only passable by motorbikes due to landslides. Sounded perfect, sort of.

We left early the following morning, aiming to get over the pass and well down the other side, and hopefully make it most of the way to Espiritu Pampa. But this photo pretty well sums up the conditions we experienced that morning. It had rained most of the night, and soon after we left Huancacalle it started really pouring. We stopped at the only open tienda/cafe in Lucma to take refuge and ended up waiting there four hours for the rain to ease.

A sucker hole finally temped us to leave and begin the 1200m climb to the pass, but of course it soon started pissing down again.

Sweaty-wet inside our jackets we steadily rode up the climb. We were feeling strong from the previous weeks’ riding at altitude combined with a day off and gained height quickly.

Gradually the rain eased off and the sun came out. It was a beautiful place to be riding as we left the cultivated country behind and climbed into cloud forest.

The views from the pass were stunning as cloud peeled back from the ridges, giving us views of the Cordillera Vilcabamba. This is a seldom visited chunk of mountain country, poorly mapped and little known. It felt like a real treat to catch this view.

Huancacalle is in the valley bottom right in the frame and the biggest peak is Pumasillo (roughly 6000m). The really pointy one further right is probably Chuqikatarpu (5512m). Abra Mojon is just out of frame about centre left. These mountains are the last ice capped range of the eastern Andes before they start steeply descending into foothills on the edge of the Amazon (right of photo).

Chawpimayu (5313m) slightly east along the range from Pumasillo.

Closer to the road we were on we could see the distinctive, vegetation covered moraine of a long-gone glacier. Seeing this made me think about how different it must have been here during the time of the Inca, 500 years ago. The glaciers would have come a lot lower, and the glaciation much more extensive across the cordillera. They’d be horrified to see the state of them now; as the permanent ice melts away with each passing decade.

The Inca worshipped Apus (the mountain gods). But they weren’t afraid of these lofty places, as evidenced by their road crossings of high passes and the ruins that are still being discovered to this day on exposed mountain ridges. To communicate urgent messages throughout the empire, the Inca maintained a line of sight communication system (using fire on exposed ridge tops) and a network of runners called chaskis who, with a mouthful of coca to bolster their energy, would run on the Inca roads to the next manned post to relay their message to the next runner.

The two-story building perched on the rocky col in this photo may have been one such way station and would likely have been crucial as an early warning station for the omnipresent Spanish threat to the Neo Inca empire who were secreted away in the jungle below. It’s called Puncuyoc, after the Cordillera it’s situated in, or Incahuasi (Inca House). It was first ‘discovered’ by American explorer Victor von Hagen in 1953, then thoroughly explored and documented during the 1970s by Professor Stuart White, and further in 1984 by veteran Andean explorer Vincent R Lee.

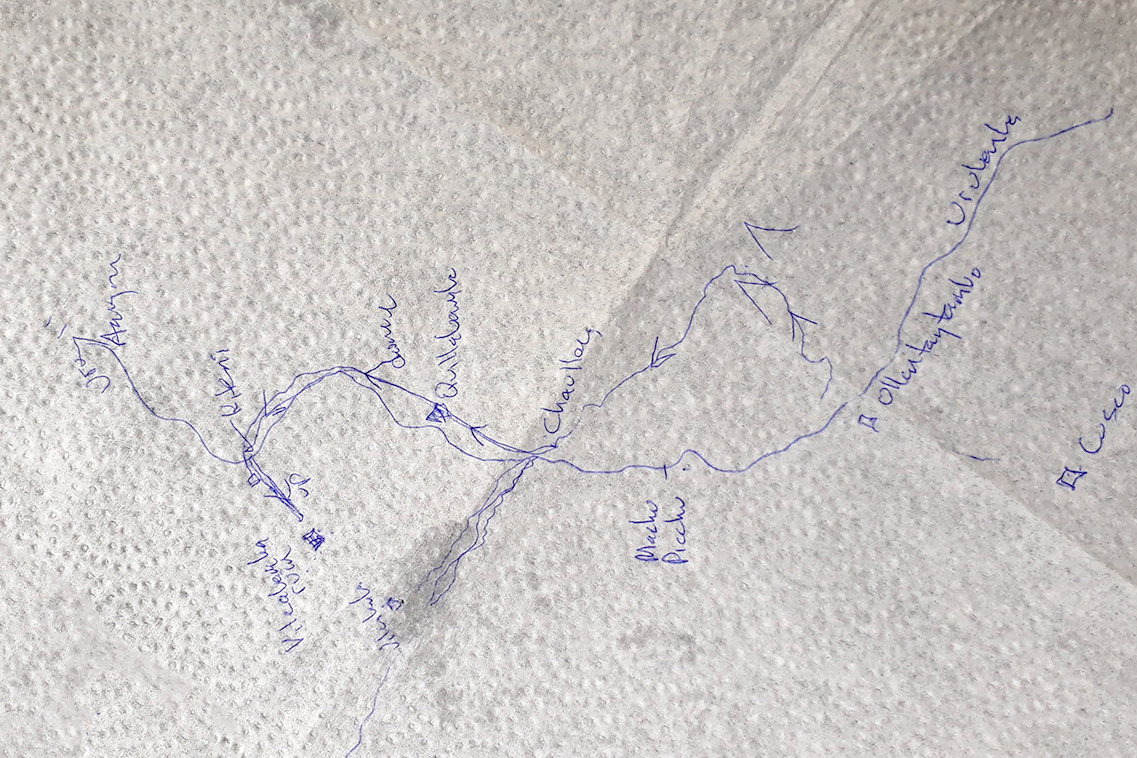

Quite by chance we’d actually met Stuart in Ecuador and it was him who’d told us about Espiritu Pampa/Vilcabamba. Stuart, who is also a paramo expert, alpaca farmer and conservationist, travelled to Peru as a young graduate student in the 70’s and lived with a Quechua family near the site of Espiritu Pampa/Vilcabamba for a year. This was near the time of its discovery and identification as the genuine ‘Lost City of the Inca’. The first we ever heard of this site was from Stuart, and over coffee in Cuenca he drew us a sketch map on a napkin and suggested we try to reach it. This meeting and map sowed the seed of the side trip we were on.

We didn’t visit this amazing looking building sadly, but reports say that it is one of the finest and most well preserved examples of Inca architecture outside of Machu Picchu. These days the thatch roof has been restored.

After absorbing the view for a long time cloud started to pour over the pass from the east, so we climbed the final part and sped down into thick mist, passing a couple of small farmhouses. We camped right on the side of the road that night on the edge of the cloud forest, as we’d not seen a single vehicle or motorbike on the road all day.

The next morning it soon became clear why the road was said to be motorbikes-only (not that we’d even seen one). Some major creeks are unbridged, and in places quite deeply washed out. You’d need a serious 4WD to drive it.

This was our final descent out of the Andes and into what the Inca called the Antisuyo; the tropical lowlands to the east that merge into the Amazon basin. For the first time since the north of Peru, several months back, we were leaving behind the high puna-type environment for a while and entering something completely different, a primal world of lichen covered cloud forest that would change into tropical forest later that day once we got low enough.

Down, to the Amazon. The forest, and particularly the ferny understory, reminded us a lot of home.

After a while our single lane dirt road merged into a much wider road that was under construction, with deep road cuts and concrete culverts. At this point it also deviated from the only route show on the map, which must have been based off an old foot trail, as we saw no sign of an older road turning off the road we were on.

We came round a bend at speed, only to see big cracks and slumps in the road bed. The last of which I ended up in because I couldn’t stop in time.

But around the corner the reason for the lack of traffic was explained: a huge, active landslide. We could see water gushing out lower down the slip and even near us sections were still crumbling away. This area too had been pounded hard by the rain we’d experienced on Abra Mojon. There was no way we could safely cross this, so we began looking for alternatives to get down to a lower switchback past it.

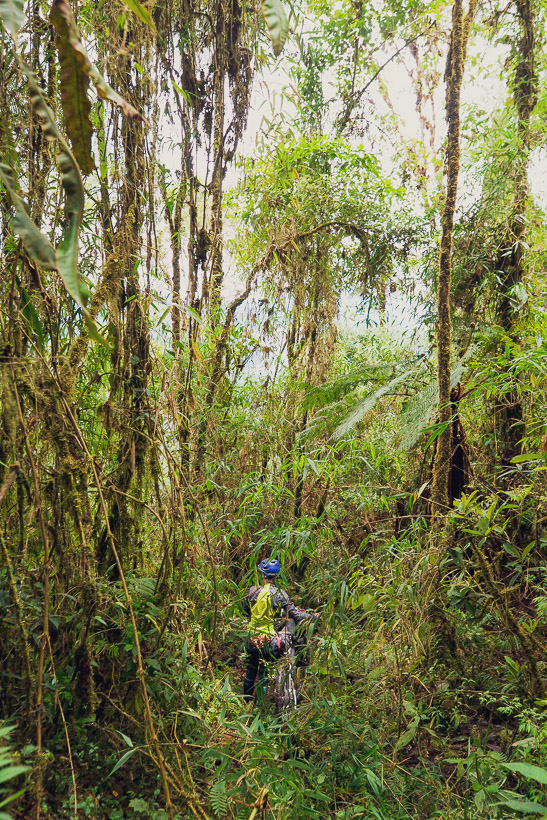

Unfortunately the mountainside was either extremely steep, or thickly covered in forest with a barely penetrable wall of bamboo beneath it. We were also a bit worried about bushbashing because of the risk of snakes. We spent about an hour climbing down two different gullies only to find them end steeply several metres above the road. They were dubious propositions on foot, let alone carrying our bikes too.

In the end we bashed a route down a bamboo-choked gully on foot, making sure it would go, and then returned for the bikes. This was still a real mission of crossing slimy fallen trees and fighting with bamboo and vines, but we got there in the end.

But we didn’t get far before we hit another …

and another …

and another! Some of these were easily passable, and even had a motorbike line, but others had fresher debris over the top.

It got worse. This one necessitated a steep climb up the bank and then a dodgy traverse across a ledge.

But right after it was this gigantic washout. I found no safe way around this one after quite a bit of exploring the forest above and below. So in the end I made a committing leap into it, landing on soft slopes and tested the climb out on the other side. Hana lowered the bikes to me which I carried up the other side and then leapt in herself. We would not have been able to reverse this.

The biggest landslide of them all came at the end, just before the termination of the main slope we were descending, but it had a safe(ish) line.

We breathed a pretty big sigh of relief when we hit this bridge and realised that the worst of it should be be over. Strangely, this section of road is an anomaly of road improvement in between what are basically two remote, single lane dirt tracks. And as a long term project it looked doomed due to the instability of the granite-sand mountainside. Later on locals told us that this happens here every wet season. Come the dry season they get a bulldozer in there to make it passable until the rains begin once again.

We still had 30-odd kilometres to ride down valley to get to a village and more supplies. A narrow dirt track led us down through a mixture of jungle and cultivated land, crossing small fords and little foot bridges.

Excellent riding.

This cantilevered bridge was a classic. Probably destroyed at least once each wet season. There was evidence of a permanent bridge being built nearby, but it didn’t look like there had been any progress for a few years.

One of the coolest things was the biodiversity we were starting to see. Cloud forest zones are supposed to have the greatest diversity of life in the transition from mountains to jungle, and we were just below that now, on the margin of the jungle. But we were seeing all sorts of weird and colourful insects. The butterflies in particular were incredible (and difficult to photograph) but we would regularly ride through great vibrant, swooping clouds of them. The blue morphos are particularly amazing; with iridescent blue wings the size of a sparrow’s wingspan.

Above is a harlequin beetle, which was a good couple of inches long in the body and the giant front legs, several inches longer.

Tucked into the forest were small farming communities and houses. Sometimes with just a patch of maize and bananas.

We reached a junction in the road and turned left for Espiritu Pampa, dropping down to cross the Rio San Miguel before climbing steeply back out the other side. At the top of a vertiginous drop to the river stood this tragic memorial to 16 people who had lost their lives in a vehicle accident there; undoubtedly an overloaded colectivo van, as is daily life in Perú. This tragedy would have hit the tiny communities here very hard.

The small farmhouses were becoming more frequent and just before dark, after an epic day, we rode into the village of Resistencia, symbolically named for the Inca resistance to the Spanish that was centred near here. We were welcomed to sit down and rest immediately by a friendly trio who were sat outside a house. It was a nice reception after a hard day, and it didn’t take long for them to agree to prepare us a meal and provide a place for us to camp under the porch of the church. Soon after we pitched the tent a meal of rice, huevos and platano arrived, along with a hot drink. Luxury, in the tiniest of jungle outposts.

There’s not much to Resistencia; just a handful of houses dotted around a grass square. The locals survive cultivating banana, platano (starchy, less sweet bananas usually eaten cooked) cacao and coffee, mostly. The village is not on any digital maps.

In the morning we were offered caldo de gallina (chicken soup) to start the day. An offer we couldn’t refuse. Besides, along with dinner the previous evening it was a chance to contribute a few soles to the local community. We ate in a basic dirt-floored kitchen, while the cuyes tucked into their breakfast too. Even down in the jungle, guinea pigs are a staple of the diet.

The road undulated onwards up valley towards Espiritu Pampa passing a couple more small settlements. Looking at this foot bridge it was easy to imagine how different things must have been in the valley just a few years ago, before the road went in.

There had been very little to buy in Resistencia, so we resupplied in a small village just a few kilometres before Espiritu Pampa. The tienda here is well stocked and we asked the girl there to fry us some eggs for lunch. There’s a small school here and at least one other basic tienda.

Finally we were getting close. Espiritu Pampa (the plain of ghosts) sits in the valley to the right. The Inca who established themselves here after being driven from their highland territory by the Spanish called it Vilcabamba.

These days there’s a small, scattered village near the site. A track climbs gently uphill until it reaches this clearing, where a few of the tallest trees have been saved. Scattered around here are the former homes of the remnants of the Inca royalty. Chased out of their homelands, but determined to maintain their fight against the Spanish, the Inca created a Neo Inca state based from this jungle hideout.

Reports from the earliest European visitors to Vilcabamba suggest there were over 400 buildings here, spread out over a site approximately 2.8 square kilometres. The Inca lived successfully here for 33 years, maintaining resistance campaigns against the Spanish, until they were overrun by a Spanish siege in 1572. The last Inca monarch, Tupac Amaru, was murdered and the city razed.

From Wikipedia: On 24 June 1572, a Spanish army, led by veteran conquistador Martin Hurtado de Arbieto, made a final advance on the Incas’ remote jungle capital. ‘They marched off, taking the artillery, wrote Arbieto in his own account of the campaign, ‘and at 10 o clock they marched into the city of Vilcabamba, all on foot, for it is the most wild and rugged country, in no way suitable for horses.’ What they discovered was a city built ‘for about a thousand fighting Indians, besides many other women, children, and old people’ filled with ‘four hundred houses’.

There’s not a lot left to see at Espiritu Pampa. Much of the site is still covered in jungle, and it’s a battle to keep that which is clear free of the encroaching forest. But it’s a poignant and powerful place to explore and acknowledge. This building is said to have been the home of Titu Cusi Yupanqui (1529–1571) who became the Inca ruler of Vilcabamba, the penultimate leader of the Neo-Inca State. Inside the walls some of the 500 year old painted plaster still remains.

My favourite spot was a separate group of ruins, further up the hill and reached with a 10 minute walk. These are less restored, covered with ferns and ungroomed. The roots of a huge tree were wrapped around one wall of a former home and there were remnants of an ancient aqueduct.

The history of Espiritu Pampa’s discovery in the modern era is quite interesting. For decades explorers sought the fabled ‘Lost City of the Inca’ because it was recorded in various histories that the Inca had established and held a final hideout and Neo Empire until the the Spanish finally destroyed it in 1572. But after that the site was completely lost to jungle.

Legendary American explorer Hiram Bingham was the first non-Peruvian to see Machu Picchu, which too had been overcome by jungle and mostly forgotten. Due to Machu Picchu’s strategic location and beauty, Bingham concluded it had to be the lost city and documented it as such. But later discoveries eventually proved him wrong.

The first known people to see Espiritu Pampa (formerly Vilcabamba) in 320 years were three Cuzqueños: Manuel Ugarte, Manuel López Torres, and Juan Cancio Saavedra, in 1892. Bingham had actually visited the Vilcabamba site not much later in 1911, the same year he saw Machu Picchu, but claimed Vilacabamba was too insignificant to have been the lost city, but in fact he’d only seen a small part of the site. It was another American, Gene Savoy with Peruvian Antonio Santander Casselli in the 1960s who finally did enough archaeology and detective work to stitch the evidence together and establish that Vilcabamba was indeed the ‘lost city’.

We spend an afternoon and early morning at Espiritu Pampa and were the only visitors. Few people make it into this remote corner of the world, but I think it probably picks up in the dry season with trekking parties coming down the valley we originally wanted to attempt.

The only other people we saw there were three maintenance workers who keep the grass short with their razor sharp machetes. We camped inside the abandoned archaeologists compound, where there is a water supply.

We were also lucky to spot a juvenile cock of the rock (Rupicola peruvianus), a bird native to Andean cloud forest. With its bright red colour and distinctive plumage, it’s widely regarded as the national bird of Perú.

Thanks to Stuart White’s inspiring story and suggestion we made it into yet another remote corner of Perú, thankful to have expanded our knowledge of this country’s incredible diversity and its rich, and at times tragic, history.

donations are welcome!

Web hosting, our Ride With GPS subscription and creating content for this site – as much as we love it – adds to travel costs and is time consuming. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content.

Thanks to Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Big Agnes, Hope Technology, Biomaxa and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

There’s certainly still a lot of scope in the world for getting into some crazy remote places. Great story and love the photo of the tent pitched at the entrance to the church.

Thanks. There is! You just have to do some planning and be motivated to explore. Lots to see out there if you’re prepared to try!

I hiked to Espiritu Pampa in 1971. You needed a permit then. No road. Gene Savoy was a friend.

What a time to visit that would have been! I wonder if I was born a few decades too late sometimes 😉