Los Llanos – Colombia’s Wild East.

This post comes from the remote river town of La Macarena, where we’ve just spent the last couple of days exploring parts of the Serranía de la Macarena, the remnant of an ancient mountain range that now forms an outlier to the Cordillera Oriental – Colombia’s Eastern Andes – jutting into the flat, tropical lowlands of Los Llanos.

Just getting here has been an amazing ride; one that’s revealed to us yet more aspects of Colombia’s rich geographical and ecological diversity as well as allowing us to witness what life is like for the isolated populations of people living here.

While the west and centre of Colombia is dominated by the two subranges of the Andes, to the east of Bogotá the landscape falls away through a series of diminishing foothills until it hits the giant plains of Los Llanos. These great plains – a mixture of jungle, savannah and grazing land – stretch into Venezuela, Brazil and to the south Peru. Walk far enough south east and you’d eventually wander into Amazona.

It was along the edge of this plain that we rode after we exited the mountains south east of Bogotá, aiming for the world renown river of Caño Cristales and the isolated town of La Macarena. This whole region, until the last couple of years, was more or less off limits for independent travel, which even now, is still a rarity. Prior to the peace treaty, signed only two years ago, between the Colombian Government and FARC (Revolutionary Army of Colombia), large swathes of this region were FARC controlled and much of their efforts in this rich tropical landscape were dedicated to coca (the raw plant precursor for cocaine production) cultivation as a means of financing their cause. At their peak, FARC controlled roughly one third of Colombia’s territory – hard fought gains eeked out of civil war that spanned more than 50 years.

As a bike packing or touring route the dirt roads of Meta Department make a classic ride. We’ve been blown away by the diversity of birdlife we’ve seen, as well as four different kinds of monkeys, crocodiles, turtles and many 4-legged mammals – some identified and some not. People are as warm and friendly as we’ve come to expect in Colombia, although sometimes it takes just a little more effort to break the ice, as people here are less accustomed to chatting with tourists.

Were it not for the suggestion of this dirt road detour by our Colombian friend Leyla, and her assurances that the security situation was stable enough for a couple of gringos on bikes, Los Llanos would have stayed off our radar, but we’re very glad we made the effort as it’s added yet another dimension to our Vuelta de Colombia so far.

It was the morning of Good Friday when we left Bogotá, the drunks and the homeless not yet awake and the roads mercifully quiet.

Bogotá’s barrios seem to stretch forever in a terracotta jigsaw of cheap, highly concentrated housing.

Once off the Bogotá Plateau and over the first set of hills we were soon on quiet dirt roads winding their way around steep mountains and farming country. The small town of Fosca had a couple of cheap hotels and made a good stop for the night.

The next morning we coasted down valley until we rejoined the main highway linking Bogotá with Villavicencio, which is unavoidable due to the heavily gorged terrain as this valley exits the Andes.

I’m not sure if this highway bridge made international news when one half of it collapsed during construction back in January, but it certainly made headlines here, with the deaths of nine workers and a trail of destruction down the mountainside.

Back in Barichara, during our first month in Colombia we met Edward and two of his children during a brief chat in the plaza. Edward invited us to stay if we made it to the Villavicencio area, but at that stage this region was off our radar and seemed a long way out of the way. With What’s App we got back in touch with Edward and we ended up staying two nights with him and his wife and various extended family.

We got straight into the spirit of Colombian life on arrival with copious amounts of Poker (Colombia’s cheap and ubiquitous beer) and a round of the equally popular game tejo, which you see courts for everywhere when riding here. A heavy steel puck is thrown by hand at two explosive triangles placed on a clay filled pit. A direct hit on a triangle produces a loud band and a splatter of clay.

Edward assured us we’d see some monkeys if we went for a short walk, and sure enough, three of these incredibly cute creatures (white-tailed titi) with their tails wrapped together were sitting in a tree in the distance (shot is an extreme crop), along with some interesting birds, known locally as pava hedionda.

We were also treated to a classic Colombian BBQ, with abundant meat, yucca, potato, rice and platano (meat and four carbs in other words).

136km of flat paved road followed the next day. To our right lay the foothills of the Andes, from which issued rivers swollen from heavy rain while to our left an infinite plain of grass and clumps of trees faded into a steamy horizon.

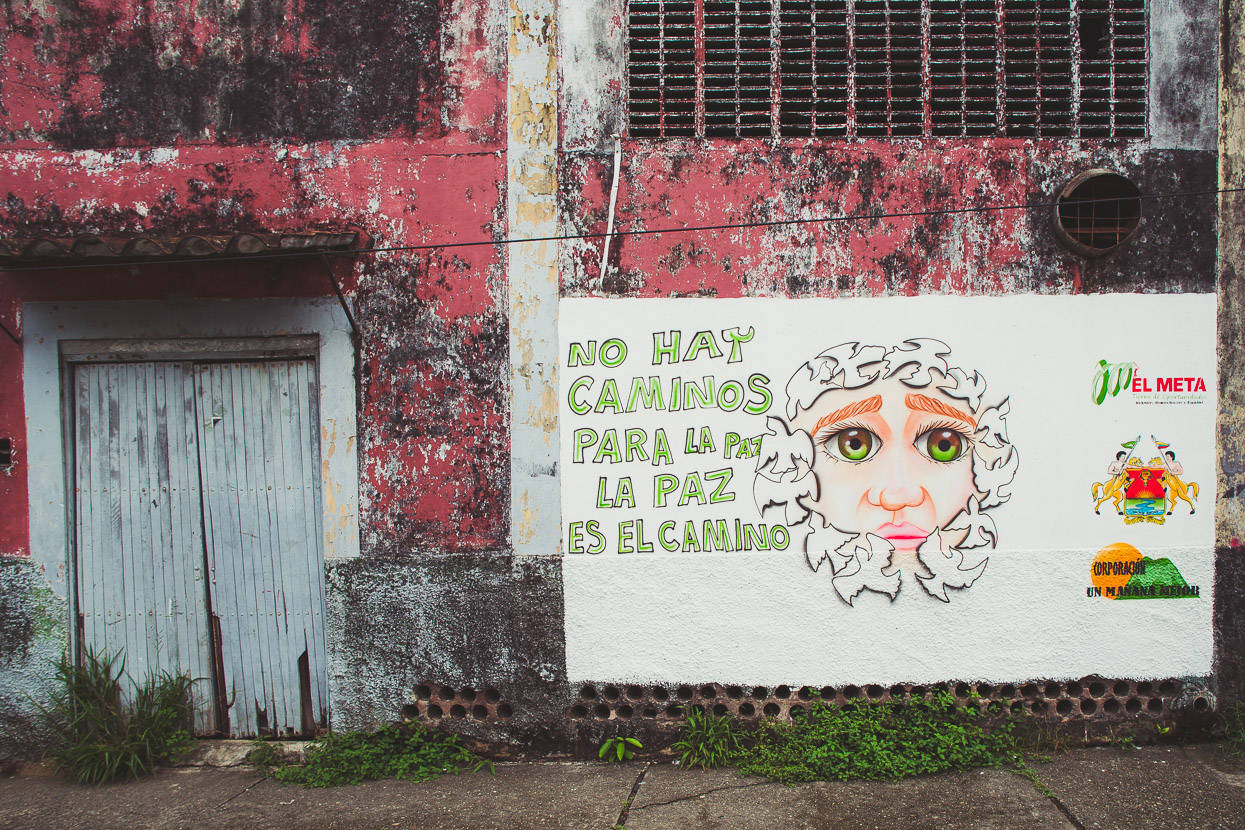

Passing though a couple of towns on the way there already the political mood that has prevailed here was obvious: ‘Don’t have paths for peace – peace is the path,’ the mural reads. Each of the bigger towns has had large military camps. Shortly before we reached Vista Hermosa we passed the basecamp for the Halo organisation, one of four NGOs working to de-mine the region, a weapon sadly very popular with FARC.

A huge – unfortunately injured – tarantula spotted on the highway.

Sandbagged gun emplacements from a military checkpoint on the outside of Vista Hermosa are a reminder that it’s not long since tensions have eased in the region. As recently as 2017 small groups of FARC militants were still ambushing and attacking police groups. The sign over the road says ‘The state of peace post conflict is possible’, while the mural proclaims ‘Territory of Peace’.

We spent the night in a cheap hotel in Vista Hermosa and the next morning turned onto a dirt road. The pavement extends a little further (apparently it takes 10–12 hours to drive the remaining 120km to Caño Cristales) but we wanted to ride closer to the edge of the mountain range as we worked our way south. A steamy haze hugged the landscape and it took until mid morning for it to burn off, leaving us baking under the hot sun in the afternoon and sweating profusely on the small, steep climbs. The road meandered its way past some small villages, through several fords (which have motorbike/pedestrian bridges) and through patches of forest. At one point we saw monkeys scuttle off into the trees.

In Caño Amarillo we were sat at a table outside a small store drinking a tinto (sugary coffee) when a woman walked by and dropped this huge mango into our hands with barely a word. ‘Un regalo?’ (gift) we asked, which was met with a nod of the head and a smile.

Our next stop was Santo Domingo, from where the road led back west towards the main route south. The hotelier in Vista Hermosa had called Santo Domingo the ‘cocaine capital’ – referring to its status during the height of FARC control of the region when it was a centre for cocaine production from the abundant crops of coca grown by the region’s campesinos. With FARC now demobilised and the cocaine source shifted elsewhere the town has slowed and decayed. The demand for coca has gone, and so has the income, leaving the town’s bars and clubs closed down and buildings abandoned – a theme we see repeated as we ride deeper into the region.

We found some empanadas for lunch and sat outside a small shop, a handful of people staring at us from under the shade of porches. The atmosphere in the town felt far from buoyant and I wondered what the people here had been through and how life here might have been under FARC.

A man sat down at a table next to us, drinking a tinto. We’d been considering taking a even more minor route further south to Palmeras or the next village, but weren’t sure about pushing our luck and didn’t want to stumble on on anything we shouldn’t. I broke the ice by asking our neighbour first about the road conditions ahead, and then we broached the topic of security. We didn’t understand all of his reply, but a shake of the head and a mention of violencia was enough to deter us.

Continuing with Plan A took us along more dirt tracks and sadly past lots of burned areas. With the demand for coco subsided, farmers are now turning to extra cattle as their primary income, which of course requires more grazeable land. Farmers under FARC control were required to maintain 20% tree cover on their landscapes, partly for environmental reasons, but also to provide cover for the guerillas. One of the prices for peace has been a significant decline in rainforest as the region’s population finds new ways of making a living.

The sun beat down on us as we skirted puddles and bumped along the track. We passed a young girl on a horse, riding slowly home from school, alone, in the middle of nowhere. Later we passed a boy, also on his way home from school, pushing a bike with a flat tyre. Harold was really shy, but happy when we offered to pump up his tyre. Back on his bike he soon sped off and then turned onto a single track that disappeared over a field to a house unseen in the trees.

Reaching a small junction village we stopped for a break and a pet baby spider monkey took a liking to Hana, climbing all over her with its lanky limbs.

We stopped for the night in Cruce de Cooperativa de Loma Linda (named as just Loma Linda on OSM maps), setting up camp in another abandoned bar. Only six families lived in this village and it didn’t take long to meet a few of the inhabitants as we sought permission to camp and found someone to cook us a meal.

Beyond Cruce the road is smaller and less well formed. Overnight it rained heavily, leaving the surface as tacky as flypaper and we only made it 800 metres out of town before giving up – our wheels seized with mud. It took an hour and a half to make the round trip 800 metres back to the village, where we cleaned up the bikes a bit and decided to wait a few hours for it to dry off. Light rain continued to fall. It wasn’t difficult to find someone to make us some coffee and cook us a meal of eggs and platano while we waited.

Not a lot happened for the rest of the morning. A single Toyota Landcruiser collectivo taxi went past (the only public transport each day) and a couple of people on motorbikes, including a guy with some chorizo, carne and pescado.

About 1pm we got started again and soon realised we’d made a good call. In heavier rain or later in the season the road looked like it would be impassable – echoing the comments made by some of the men in town about peak wet season here, which in early April we were just on the edge of.

Loma Linda itself was nothing more than a school and a couple of houses. School was out for the day but the teacher who lived out the back was pottering around and we stopped to ask her for some water. The conversation soon turned to people’s difficulties in the area now that their cash crop is no longer and the people have dispersed. We commented how big the school looked and then realised the sturdy concrete building with a counter top in the centre used to be a bar – apparently in the middle of nowhere.

Shrapnel marks in the concrete of a blown up bridge

We stopped late in the afternoon in El Avion (also called Alto Avion by the locals), a small outpost of a few buildings, a tienda with very limited supplies and a basic restaurante y residencias where we spent the night. The rooms and restaurant – with no electricity or running water – were run by Monica and Diego, who lived there with Monica’s sister and her husband. Dinner for the evening was whatever was being cooked by the family. You don’t expect a menu or any choice in this kind of place.

Leaf cutter ants make a trail of leaf segments across the road. It’s impossible not to run a few over, but at least it feels like payback for the little buggers eating holes in the floor of our tent.

After El Avion we entered the national park proper, but were amazed by how much of it has been (apparently recently) burned, especially along the road margins. This section wasn’t quite as scenic as we’d hoped, but some stands of taller trees remain by the road and we saw over a dozen toucans, in three different varieties.

Yarumales was a bigger village than we’d been expecting; there’s a hotel, a restaurant and a couple of tiendas (with very limited supplies).

Beyond Yarumales we stopped at Caño Canoas, one of the national park’s better known rivers. We’ve come to realise – since Mexico even – that places with fresh water (or any bathing water) are very popular with locals in the tropics, and places with waterfalls – even small and unspectacular ones – are revered. Caño Canoas was a special spot though, with an Eden-like atmosphere of cascading water from several falls, lush forest, warm sandstone and water that’s a perfect temperature.

After Canoas the road deteriorates right down to a motorbike track in places, although still passable by 4WD in dry-ish conditions. It makes for some great riding through sections of thick forest. We’d been expecting the road to improve this close to Caño Crystals, but not so, despite people a day or two back telling us the road was good or that it was ‘plano’ (flat) – which it most definitely isn’t!

An hour before sunrise we finally crossed the Caño Cristales river, followed by a chain of horses. We continued to the few buildings that make a primitive restaurant and hospedaje nearby, introduced ourselves, parked the bikes and went back to the river to catch sunset. It’s a magical spot. At the Los Ochos formation, just a little upstream from the crossing, water has worn huge holes and fissures in the ancient sandstone creating a labyrinth-like formation of rock brought to life with running water.

During the months of June–September this special river attracts visitors from all over the world to see the remarkable red and green algae-like plants that flourish in the pure water, turning it into a spectacle that you (apparently) can’t see anywhere else in the world. We were here off-season, but this place is still amazing to visit even at this time for its unique combination of biodiversity – a nexus of the ecosystems of the Amazon, the Andean and the Orinoquian.

Being the off-season for Caño Cristales we had the run of the place. The couple who ran the hospedaje were happy for us to camp on the porch for nothing. We were the only tourists there and the only other person we saw apart from the handful of people who live there was a single soldier. Basic meals are available at both the restaurant closest the river (overpriced) and the kitchen that’s next to the hospedaje (great value). We were up early in the morning but it started raining, so we took a hearty second breakfast of hot chocolate, huevos, rice and platano.

The Serranía de la Macarena formation itself is a great, gently titled slab of sandstone – a heavily eroded remnant of land from the Pangea supercontinent that’s significantly older than the Andes. It’s a particular kind of savannah landscape, with shallow soil cover and unique plants specialised to recover quickly from fires. The forest is quite open and doesn’t reach the lofty heights of full jungle.

Normally a guide is mandatory and tourists pay a park fee for the river but we were free to wander and explore by ourselves; spending the morning walking through the savannah and riverbed. The river has three branches, each with a series of named cascades which are marked as POIs in OSM. Even without the famous colourful river plants it’s a remarkably beautiful place, where you could easily spend a day soaking in different rock pools.

The road onwards to the township of La Macarena continues as a sandy – sometimes bedrock – track, even now with a fair bit of water around. I’d been bitten or stung by something back at the river – I think a large ant, and some minor itching and redness progressed into some quite dramatic swelling around my glands; my groin, armpits and the two sting sites were all quite inflamed by the time we reached the deserted river bank just a couple of kilometres from town – which was on the other side.

The Guayabero River.

Fortunately a passing canoa picked us up, so after finding a room for the night we headed to the farmarcía where I got an injection of betamethasone in the backside.

La Macarena is the only sizeable town in this neck of the woods and all roads that lead to it are dirt. It’s a crucial service town for the far flung and isolated farms of this region, as well as the location of a 4000-strong military base and airfield. The base, bristling with lookout towers and aerials, lies on a small hill on the edge of town and soldiers patrol the streets with assault rifles. On first glance it’s an uneasy sight, but over the three nights we spent in La Macarena, despite the military assertion of control, we found the townsfolk to be relaxed and friendly and the town had a positive vibe. By the time we left we could barely walk down the road without bumping into someone we’d met.

A memorial to Colombian soldiers killed in actions against FARC in the immediate area. There were several hundred names on the memorial, spanning 2004–2015.

We did a couple of day trips out of La Macarena to explore more of the Serranía de la Macarena and I’ll write about those, and the rest of our continued dirt ride back towards the Andes in the next post.

Do you enjoy our blog content? Find it useful? We love it when people shout us a beer or contribute to our ongoing expenses!

Creating content for this site – as much as we love it – is time consuming and adds to travel costs. Every little bit helps, and your contributions motivate us to work on more bicycle travel-related content. Up coming: camera kit and photography work flow.

Thanks to Biomaxa, Revelate Designs, Kathmandu, Hope Technology and Pureflow for supporting Alaska to Argentina.

Very cool! By the way, those are probably termites not bees! And yes, in the USA we did hear about the bridge disaster: https://imgur.com/gallery/IjprH

Thanks David – I thought termites, but the locals saw the photo and said bees… They’re mistaken maybe?

A bit late, but thought some followers might enjoy this: https://www.dropbox.com/s/c1a3nxkkrdfpeg6/Mark%20%26%20Hana%20Las%20Nevados.mp4?dl=0

Decided to fly your GPS route in Google Earth, so as to get a feel of the mountains. You two are truly adventurers!!

https://www.dropbox.com/s/37idyhg64v9n0io/Bogota%20to%20La%20Macarena%20Flight.mp4?dl=0

Absorbing reading, as always. No, we didn’t hear about the bridge disaster. But just last week on National News we saw a bunch of refugees from Colombia, which the Govt are sponsoring & setting up in – Invercargill (!) Through an interpreter they spoke eloquently about Sparc & because they feared for their lives, the need to leave Colombia………just what you have written about in this blog. (9.14pm the house has just been rattled with an earthquake) Hope the injection worked ?

Hi Madge – thanks for your comments – always nice to see. Yes the injection worked – although it took a few days to totally clear up. Interesting to hear there are Colombian refugees settling in NZ. At the moment thousands and thousands of Venezuelans are pouring into Colombia each week. We keep meeting them too!

I’m following in your footsteps again, currently in Fosca. Loving this part of the country. The woman who made my dinner tonight said I was the first gringo she had ever seen here.

Classic! What happened to your Caribbean plans? Oh well – Los Llanos is just as hot… 😉 Have fun.

I did not realize that I needed the yellow fever vaccine to get into Aruba until it was too late. Spent a nice weekend in Medellin instead. I’ll be in Quito 5/15.

Oops! You wouldn’t be the first. Hope Los Llanos is good and you don’t get mud… We’re in Mocoa now and it’s raining heaps. Headed to Pasto over next 3 days.